|

The World's First Working Universal Turing MachineThe

story of the Manchester computer begins at Bletchley Park in

1944. There, the Cambridge mathematician M. H. A. Newman had

determined the function and organised the use of the Colossus

electronic machine (see this Scrapbook

Page) for breaking the top-level German strategic

messages. In 1945 he became Professor of Pure Mathematics at

Manchester University, and had ambitious plans to make a

powerful new department there. In particular he hoped to take

advantage of what had been achieved at Bletchley Park, and

turn it to peaceful scientific research.

In 1935 it was Newman who had introduced Turing to the

problem which led to the Turing machine (see this Scrapbook

page), and Newman was the first person ever to read of

Turing's universal machine in 1936. Now the war had proved the

reliability and speed of electronic digital technology. Max

Newman was a pure mathematician, but the war had given him,

like Turing, a vision of what an electronic computer could do;

and he was fully aware of the power of Turing's universal

machine concept.

Unlike Turing, however, he had no interest in getting

involved personally in electronic engineering.

Newman acted swiftly. In February 1946, as you can read

more about in my book,

Newman wrote to von Neumann that he was

hoping to embark on a computing machine

section here, having got very interested in electronic

devices of this kind during the last two or three years. By

about 18 months ago [i.e. soon after D-Day, and a year

before von Neumann's EDVAC report] I had decided to try my

hand at starting up a machine unit when I got out. It was

indeed one of my reasons for coming to Manchester that the

set-up here is favourable in several ways... I am of course

in close touch with Turing...

Note that at this date, Turing had not even had his ACE

proposal accepted by the National Physical Laboratory; these

were very early days.

Newman's intention was that the machine would be used for

pure mathematical work in algebra and topology, for instance

the Four Colour Theorem. The Royal Society approved the

project and allocated a grant to Newman for salaries and

construction totally £35,000 (about a million pounds in real

terms now), with the comment that 'Newman himself, because of

his mathematical background and wartime experience, is

particularly well qualified for directing this project.'

At that stage, early 1946, Newman expected that that the

American Iconoscope would become available as the storage

system. But it didn't work. Meanwhile at the radar

establishment, TRE, the top electronic engineers had found

themselves suddenly out of a job in August 1945. F. C.

Williams looked around for a leading-edge project. He soon

heard that the possibility of building electronic computers

was in the air and that creating a storage system was the main

technological bottle-neck.

He had a bright idea for storing digits as bright spots on

a screen. The Williams

tube converted the cathode-ray-tube into a viable storage

medium for digital information.

In November 1946, Williams was appointed to the chair of

electrical engineering at Manchester.

Newman's idea was that it would be advantageous to exploit

Williams' work on cathode-ray-tube storage, even if, as it

then appeared likely, an on-site development would take longer

than the Americans. Newman had no rigid ideas about hardware,

and simply wanted a computer built by the most effective means

possible.

In fact, Williams and his assistant Tom Kilburn did it much

quicker than anyone expected. In June 1948 a 'baby machine'

was working. It could store 1024 bits on a cathode-ray-tube,

enough to demonstrate the stored-program principle in working

electronics, the first in the world to do so.

Meanwhile in March 1948, Newman had offered Alan Turing a

post. In May 1948 Turing gave up hope of the National Physical

Laboratory turning his Universal Machine into practical

reality (see this

Scrapbook page for the ACE machine that Turing designed).

He resigned from the NPL and accepted relocation to

Manchester, where this breakthrough had rather unexpectedly

been achieved.

The salary for Turing's post came from the Royal Society

grant. He was formally 'Deputy Director' of the Royal Society

Computing Machine Laboratory. The grounds for appointing him

to this post, as minuted on 15 October 1948, were that

It was in his paper on 'Computable Numbers'

(1936) that the idea of a truly universal machine was first

clearly set out. This paper was written for purely

theoretical and logical purposes, but Mr Turing has had over

two years of practical experience since the war, as designer

of the ACE machine which is now being constructed at the

National Physical Laboratory. Thus as the

time of his appointment, the character of the Manchester

machine as a practical version of the Universal Turing Machine

was made clear. It was soon totally forgotten.

|

Who had the Idea?The Manchester computer of 1948 has

been reconstructed for its fiftieth

anniversary on 21 June 1998. There is much information on

the Manchester site about how Williams and Kilburn succeeded

with their cathode-ray-tube storage and built the machine.

Brian Napper, who has written the material for the

Manchester site, stresses in his page

on the general background that the Manchester machine was

built with programs loaded in RAM --- the revolutionary idea

that defined the computer. (See this

Scrapbook page.) But he doesn't explain how Williams and

Kilburn got this idea.

It would have been possible for Williams to learn about the

stored-program principle in the course of his 1946 work at TRE

on the storage mechanism. It was generally in the air after

the EDVAC report of 1945; and from Turing's ACE proposal. But

what in fact happened, according to Williams (in the

Radio and Electronic Engineer, July 1975) was

that he learnt the principle from Newman after taking up the

Manchester post in December 1946.

With this store available, the next step was

to build a computer around it. Tom Kilburn and I knew

nothing about computers, but a lot about circuits. Professor

Newman and Mr A. M. Turing knew a lot about computers and

substantially nothing about electronics. They took us by the

hand and explained how numbers could live in houses with

addresses and how if they did they could be kept track of

during a calculation...

There is an obvious chicken-and-egg interdependence between

logical function and practical engineering. Turing and Newman

could not embody their ideas without engineers; the engineers

would not have known what to build without the mathematicians'

ideas.

I feel that the latter aspect is not always given its full

weight, but mathematicians are very modest people.

|

Carry on Computing

At Bletchley Park, in building Bombes and the Colossus, the

synthesis had been reasonably harmonious but it was not to be

so at Manchester. There was a particularly Mancunian culture

clash.

Alan Turing could not 'direct' anything, but he organised

the software which made the engineers' machine work. In 1950

he completed a Programming Manual.

An

opening segment of the second edition of this Manual is

available on the Manchester site in an HTML rendition.

A

complete version of the first edition will appear later

on-line. A preliminary draft can be found now on this MIT

site, with an introduction

by the editor, Robert S. Thau adding comment on Turing's

programming ideas and their context.

Turing's assistants on the software writing were women,

Cicely Popplewell and Audrey Bates. This set-up neatly

confirmed Manchester stereotypes:

| hard |

soft |

| engineering |

mathematics |

| Williams, Kilburn |

Newman, Turing |

| things |

concepts |

| north |

south |

| Real Manchester |

Virtual

Womanchester |

Has much changed? At least women in

computing and gender

issues are on the agenda.

War Again

The British government desperately wanted atomic bombs.

They didn't believe that the Americans would retaliate against

a Soviet nuclear attack on Britain, and they wanted to prove

that Britain was still in the Big Three. The 1946 McMahon Act

in the United States meant that Britain, which had given much

to the wartime atomic bomb programme, was denied American

co-operation thereafter. In late 1948, the Cold War began in

earnest, and it became a British national priority to have

computing facilities for the atomic bomb implosion

calculation.

A lavish new contract was rushed through to allow Ferranti

to build a full-scale machine, the Ferranti Mark 1. The

contract specified merely that it would be built to Williams's

design.

Newman's priorities for pure mathematics and science were

forgotten. |

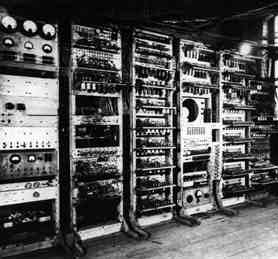

Fifty Years of HardwareThe prototype computer looked

like this:

and there are many more on the pictures on the Manchester

site, which also includes a history of

Manchester computers from 1948 to 1975.

There are also more

photographs maintained by Tommy

Thomas, one of the engineers of the original project.

|

Parallel machinesAt this period the main rival to the

Manchester computer development was the EDSAC computer

at Cambridge, England, inaugurated in September 1949. This was

the work of Maurice Wilkes, who took as his starting-point the

American EDVAC proposals, but was able to beat the Americans

at their own game.

Turing gave a talk at its inauguration which anticipated

later ideas of program proof, but, in typical disregard for

his own reputation, made nothing of it.

There is a description and

simulator of the EDSAC by Martin Campbell-Kelly.

A version of Turing's ACE design was built at the National

Physical Laboratory after all. The Pilot ACE was inaugurated

in November 1950. It is now in the Science Museum, London;

which has a picture of it in its virtual

gallery of Treasures. |

Using the world's first computer F. C. Williams

himself had no interest in the use of the machine he had

built. Speaking in an oral history of Pioneers of Computing,

Science Museum, 1976, he said:

Well let's be clear right from the start, I

never have been interested in computing, and I'm still not

interested in computing. What I'm interested in is

computers. I'm an engineer, I define the computer right from

square one as a device which was designed to facilitate the

performance of mathematics, the greater part of which would

be very much better not done, and I've never changed that

view really...

Users were seen as rather a nuisance while the machine was

in development, but Newman immediately found a genuine

mathematical problem that could be run on the prototype

Manchester computer, and thereby rescued a little of the

originally intended function for the machine in pure

mathematics.

This was the problem of finding Mersenne

primes.

At that time the largest known prime was

2127 - 1, and had been so since

1876, when Lucas discovered a test for primality of numbers of

this type, a test which was extremely well suited to a

computer. They ran a program successfully, and then Turing

coded a faster version of it, but even so did not discover the

next prime, which was out of range at

2521 - 1, and was found only in

1952.

The largest

known prime now is again a Mersenne prime, and found by

exactly the same method, only on a somewhat larger and faster

computer).

The 1949 programme gained newspaper publicity for the

Manchester computer, although (or because) readers of the day

would have assumed prime numbers to be the epitome of pure

mathematical uselessness. Nowadays these investigations are

seen rather differently because of the connection between

large primes and cryptographic security. As usual the

mathematicians were ahead of their time.

It wasn't that either Newman or Turing had a particular

research interest in Mersenne primes; the problem was chosen

as one which could show off the power of the computer. But in

1950 Turing used the prototype computer for a problem which

derived from his pre-war research work on the Riemann

Zeta-function, also associated with the properties of prime

numbers. This was probably the first serious use of a computer

for research in mathematics. For Turing it also illustrated

very neatly the power of the universal machine concept, as it

performed the work for which he had designed a special-purpose

calculator in 1939, now made completely

redundant. |

Intelligent Machinery comes out of the ClosetAlthough

Newman made very careful statements to the press, Turing as

usual announced rather incautiously that what they were

interested in at Manchester was the extent to which a machine

could think for itself.

This provoked an immediate response from a Manchester brain

surgeon, Geoffrey Jefferson, in 1949: a lecture with the title

'No Mind for Mechanical Man.'

Alan Turing was stimulated by the public controversy to

write a definitive paper on his views for the prospects for

Artificial Intelligence, or as he called it, Intelligent

Machinery. This paper, introducing the idea of the Turing

Test, was his only paper on the subject to be effectively

published. He took the opportunity to air a kind of wit which

could hardly have been more different from the heavy macho

engineering ambience at Manchester, and in which male and

female role-playing enjoyed a curious part.

You will find this paper described on another

Scrapbook page.

He also gave a talk on the BBC radio Third Programme:

although the producer had strong doubts about his talents

as a media performer. |

New growthAlan Turing made the best of a bad job, and

settled in Manchester. He bought a house some ten miles south

of Manchester near the small town of Wilmslow, Cheshire. He

often used to run in to work rather than take the train.

Meanwhile, by 1950 Alan Turing had moved on with a

completely new idea: a theory of biological growth and the

beginning of computer-aided non-linear dynamics.

|

| |